When considering cultural appropriation, Coachella attendees donning headdresses and unflattering images of individuals partaking in offensive costumes often arrive in the mind. We’re looking at you, Justin Trudeau — don’t worry, you’re certainly not alone.

High-end fashion brands borrow patterns and sacred designs from the tapestries of indigenous people with nonchalance. Urban Outfitters mannequins in the suburbs mirror the fashion of inner-city youth. These are the facts.

Cultural appropriation, at its core, is deemed an insolent, unoriginal act often seasoned with the special herbs and spices of prejudice. Of course, not everyone that partakes in the appropriation of existing culture is an insensitive vulture. Sometimes, appropriation is more so an act of adaptation. Some of these cases occur when historically marginalized communities take on the fashion styles of dominant social groups – not in an act of subservient assimilation, but in the name of cultural reclamation.

Jazz legends and today’s NBA superstars alike elevated prep and traditional fashion far beyond the east coast Ivy Leagues universities they originated from. Uniforms of Harvard business students and the suits of Wall Street prowlers found themselves in smoky LA clubs and post-game interviews. Rather than replicating these looks, these vanguards of both yesterday and today create a standard of cool.

The Birth and Burial of Cool

There was once a time before hip-hop. Though difficult to believe, trunks of middle America sedans have not always rattled to the rhythm of booming bass and hi-hats.

In the era B.K. (“before Kendrick,”) there was jazz, the first authentically American art form — also known as hip-hop’s well-dressed, cigar-smoking grandfather. Through time, jazz took on many forms: cookie cutter to Avant-garde, from popular to underground.

Regardless of what record sales may indicate, jazz hit its true prime in the 1950s in spite of its competition with its more popular cousin rock & roll. Jazz was not intended for solely the popular, though. It was bespoke for the cool. Just as it talked the talk, jazz walked the walk and looked the look throughout the ’50s and later through the 1960s.

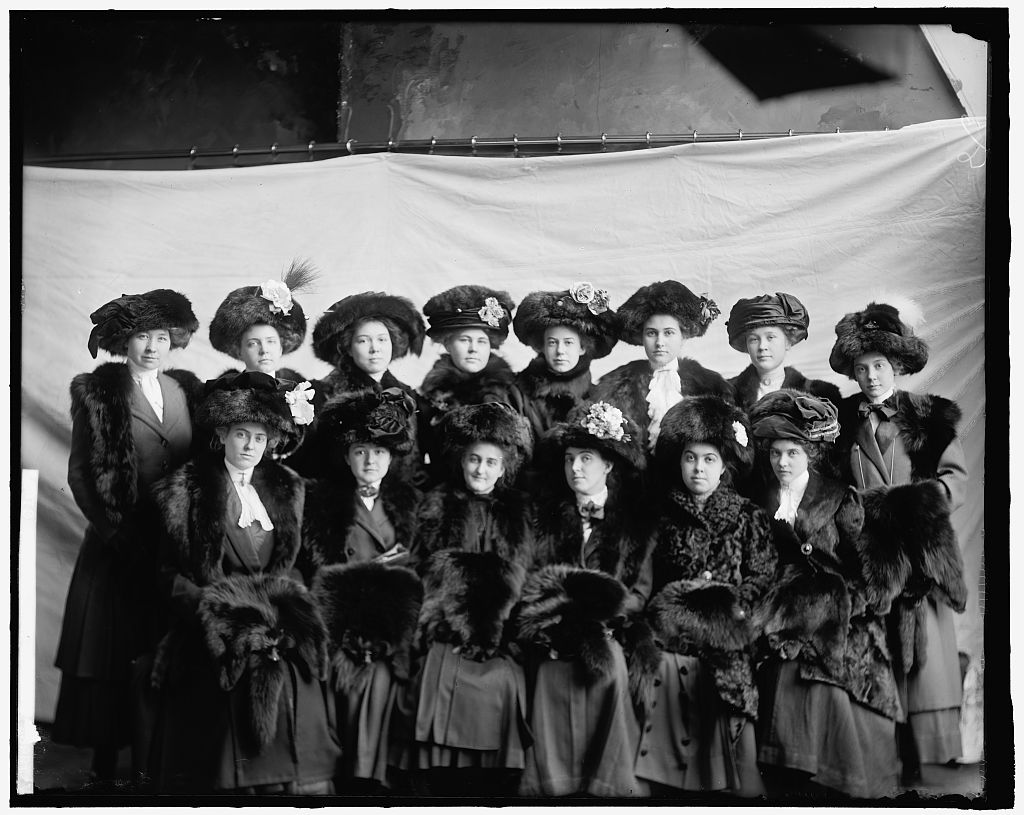

Thanks to the efforts of the era’s civil rights activists, Black Americans were taking hold of American culture as their own. Though only a few decades removed from the days of minstrels, emerging jazz artists and enthusiasts of this era elegantly disassembled the stereotypes formerly attributed to Black people. These individuals married Ivy League with the unadulterated flair of Kansas City, New Orleans, Harlem and African ancestry.

The coolest of the cool to sport these fashions is the one and only chief: Miles Davis.

If you are unaware that Miles Davis is one of the best musicians of all time, don’t look to be educated any further on his music here. Just know that Davis’ trumpet playing, composing and arranging was just as great as his style. Like his musicianship, Davis fostered his fashion sense early on.

“Dr. Davis (Davis’ father) would buy his son fashionable clothing throughout his teen years,” authors of Clawing at the Limits of Cool Farrah Griffin and Salim Washington wrote.

“Well-dressed children were a source of great pride to African Americans, not only because they were a demonstration of their parents’ prosperity, but also because personal style and grooming made a public statement about the ‘race.’”

Well-dressed children were a source of great pride to African Americans, not only because they were a demonstration of their parents’ prosperity, but also because personal style and grooming made a public statement about the ‘race.’” – “Clawing at the Limits of Cool” by Farrah Griffin and Salim Washington

As Davis grew older, the clothes that he purchased for himself were on par with what his father fashioned him in. His stylings appreciated from afar, and they became the core of the culture.

“Miles Davis, the coolest man on the planet during his Ivy-suited period was probably most responsible for both the ‘look and sound’ of Modern Jazz,” Port Magazine’s Graham Marsh wrote. “Miles used to get most of his Ivy clothes from Charlie Davidson’s Andover Shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just off Harvard Square.”

With an undeniable penchant for clothing that rivaled the looks of his Hollywood friends such as Steve McQueen and Dennis Hopper, Davis made his efforts to be heard and seen quite well known. Paving the way for current style royals, Davis set trends each and every time he graced a stage. “If Miles wore it, it was instantly hip,” Marsh said.

What else would you expect from the man who recorded “The Birth of Cool?”

Then, the cool became hot.

Davis’ style became increasingly eccentric and Afrofuturistic – and the tribe always follows the chief. Movements of the late ’60s drove the hippest Americans to trade seersucker sport coats and khakis for tie-dyes, furs, black turtleneck sweaters and even blacker berets. Natural hairstyles took priority over the arduous routine of hair-processors.

The second wave of American urbanization found individuals in marginalized communities embracing their own cultures rather than the “preppy” look of the dominant society, and this late-’60s attitude continued to rise and bubble over into the modern era.

Carlton’s Lament

By the 1990s, many minoritized people considered Ivy League fashion as certified vanilla, corny and synonymous with one name: Carlton Banks. The most influential Black artists were R&B singers and rappers, no longer playing trumpets or wearing leisure suits and loafers. Hoodies, baggy jeans, Timberland boots, and Jordans fit the culture a bit more accurately.

So where did that leave the minorities with an affinity for prep? Well, that’s where Carlton comes in. Best known for his swinging, snapping dance and love for Tom Jones, “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” character Carlton Banks, portrayed by Alfonso Ribiero, embodied Black prep.

The memorable suburban foil to the West Philadelphia-born and raised Will Smith, Carlton represented the antithesis of Black authenticity. His cardigan Polo sweaters tied around his waist were not “down with the culture,” and, until recently, weren’t seen as such.

For a stylish person of color who grew up in predominantly white Fort Collins, attends a predominantly white institution and pursues a career in a predominantly white profession, Tinotenda Makombe resonates with Carlton’s ethos to a degree. However, Makombe does his best to subvert the look. Makombe is a first-generation American, his family hailing from Zimbabwe.

“Being in the business school, it isn’t an out of the ordinary to see someone in a suit or dressed preppy around Rockwell,” Makombe said. “But when someone sees me in a suit in the food court, just eating some Panda Express, I’ve had people come up to me and ask, ‘Why are you all dressed up?’ or ‘Why are you dressed white?’”

Makombe’s defense: “I’m just dressed for the occasion!” His occasion? The opportunity to look good in a way true to Tino.

“Nothing should be considered anything based solely on race, just because it’s nice or looks good,” Makombe said. “That’s why I do it my way.”

Adaptation

Freshly braided locks fall upon Makombe’s forehead. A gold ring graces his nose and matching gold cross earrings sway from his earlobes. He sports a gold chain pendant of his home country around his neck.

An aspiring financing accountant, many wouldn’t deem Makombe as one who epitomizes traditional dress. He knows he stands out, and quite frankly, he doesn’t care. He embraces it.

“When dressing up or fitting into traditional wear, there is a certain uniformity that’s anticipated, and I live up to it, but I also exceed it,” Makombe said.

With his jewelry, hair and top-tier taste, Makombe takes traditional prep to new heights.

Many other young black men have done the same. No longer corny, the most stylish NBA players such as Russell Westbrook, Chris Paul and LeBron James, as well as entertainers Michael B. Jordan and Donald Glover have given new meaning to the trad look.

The future of trad dares to pair tattoos with topsiders, locks with loafers and blazers with hoodies.

Oh, and this future is not solely reserved for men.