Ad

Asian American Culture in Old Town Fort Collins

The Cache la Poudre River provides the water necessary for irrigation of local farms. Japanese immigrants coming into Fort Collins in the 1800s and 1900s worked to create the irrigation systems used today for agriculture and residential use. (Gregory James | College Avenue Magazine)

April 27, 2022

Those familiar with Colorado probably don’t know that iconic Old Town Fort Collins, which is both a popular college student hang-out as well as a booming destination for tourists and locals, used to be a hub for eastern Asian immigration.. Old Town Fort Collins was once home to an Asian community during the Gold Rush, and later, was the workplace for a significant number of Japanese immigrants who worked for agricultural ditch companies. Today, Chinese restaurants and businesses carry the remnants of this era through the town we know, and Fort Collins farms still rely on infrastructure built by Japanese immigrants.

When the discovery of gold in California met the ears of Chinese men around the late 1840s, they, along with many others, were drawn west to capitalize on the idea of striking it rich. The large migration led to the first transcontinental railroad. Many others, especially those who hadn’t been so lucky in finding gold, turned to the railroad sector. This included many of the Chinese immigrants who were now in America. As railroads began popping up throughout the country, so did Chinatowns, which were areas of large cities and towns in which the population was predominantly of Chinese origin. Fort Collins quickly became one of the various Colorado Chinatowns, in addition to Denver.

“One of the problems with this kind of history is that, if it was documented at all, it was being documented by mostly white middle class journalists who weren’t exactly interested in the history of Black or Asian communities, especially in the late 1800s,” Jim Bertolini, the historic preservation planner for the City of Fort Collins, says.

According to Bertolini, the Fort Collins Chinese community was likely located near the north side of the railroad tracks around present day Willow and Linden streets. The first of many Chinese businesses in Fort Collins was Yee Lee’s Laundry, which opened in 1881. Even after Lee moved to Rock Springs, Wyoming, Yee Lee’s Laundry stayed in operation, carrying Asian-American business through the next several decades of Fort Collins history. It wasn’t until the 1920s that the laundry closed and was turned over to a white entrepreneur. Unfortunately, the Asian-American impacts on this area were not preserved, and The Perennial Gardener is the current business that resides where Yee Lee’s Laundry used to be.

A small laundry may seem trivial, but the time just before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which temporarily suspended Chinese immigration and made Chinese immigrants ineligible for naturalization, was extremely dangerous for the Chinese community. The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed because American society used the Chinese people as scapegoats for the poor wages and lack of jobs, even though they only accounted for .002% of the population. The exclusion act demonstrated the immense amount of hatred for the Chinese community during this time.

“These are a small handful of Chinese residents that choose to stay, because this was a pretty hostile environment for anyone of Chinese ancestry,” Bertolini says. This made the Chinese businesses that sustained themselves through that era that much more historically notable.

Although there was still significant Asian immigration in the late 1800s, the Chinese Exclusion Act shifted immigration demographics from Chinese to Japanese. With the lack of records from this time, it is hard to say for sure which types of businesses were here. However, Bertolini suspects that there was a Japanese boarding house, which is a house where lodgers rent single rooms on a nightly basis, in Fort Collins at one point. This would have been located at 228 Jefferson St.

“There’s a boarding house that operated on the upper floor, and we think that might have been a boarding house for Japanese migrant workers,” Bertolini says.

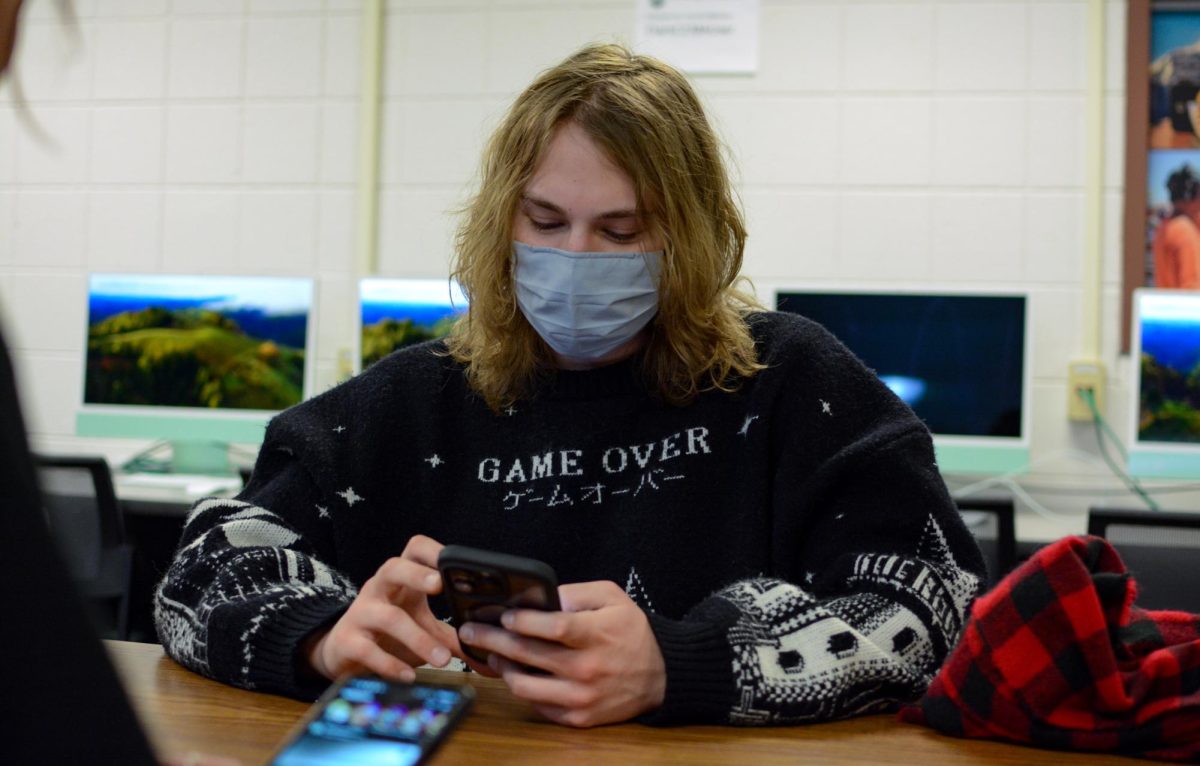

These Japanese immigrants worked primarily in agriculture, developing irrigation and ditch systems throughout Northern Colorado. Many of these ditches are still in operation today, and they usually support and provide local farms with water. They also provide current Fort Collins residents with drinking water.

“Since they were moving around a lot, they weren’t living in permanent apartments or houses, so we think the Ukata rooms at 228 Jefferson might be [boarding for the Japanese workers], because that is a Japanese surname,” Bertolini says.

The Japanese community in Colorado grew to a noticeable size in the 1920s and caught the eye of the Klu Klux Klan. In 1924 Clarence Morley, Colorado governor and Klu Klux Klan member, passed multiple laws that limited the rights of the Japanese community, including preventing them from owning and buying land. The inability to buy land forced many to move, and this significantly decreased the Japanese population.

The Asian American impact in Fort Collins is not exclusive to the late 1800s and the Gold Rush. Asian American culture is carried through Fort Collins today through the businesses and restaurants that have developed and operated over the years, primarily from Eastern Asian immigrants to Fort Collins. This includes LuLu Asian Bistro, formally known as The China Palace. According to Bertolini it was opened by Walter Wang, who was a Ph.D student at Colorado State University in the 1970s. Further, the University brings the Asian American culture to the campus with its Asian Pacific American Cultural Center, which educates and spreads awareness to the community and students. They also provide support for Asian American and Pacific Islander students.

The Asian American history in Old Town Fort Collins may not be evident, but the contributions of Asian Americans during the 1800s impact modern Fort Collins. The Asian American heritage is almost as old as the town itself.

If you would like any additional information about the vivid Asain American history of Fort Collins, you can email the City of Fort Collins’ historic preservation program at preservation@fcgov.com to learn more.