Ad

The Aggie Era: CSU’s Beginning History as an Agricultural and Mechanical College

September 21, 2022

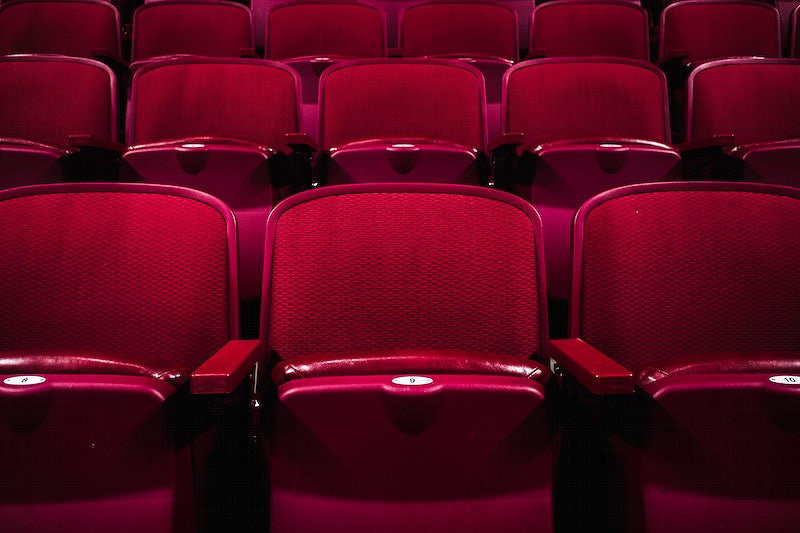

As one strolls through Colorado State University, they see ”Ram pride” everywhere: green and gold banners are posted on the walls, murals of CSU glory painted near the Lory Student Center, and CSU alumni portraits hanging in the Andrew G. Clark Building. Cam the Ram, CSU’s beloved mascot, can be found at football games, surrounded by handlers. The stands are a wave of green and gold, accompanied by excited shouts of students screaming, “Proud to be a CSU Ram!”

And yet, instead of a giant “R” marking the mountains in the distance, symbolizing our beloved mascot, there’s an “A.”

Before we were the Rams, we were the Aggies. CSU’s “Aggie Era,” one of its most prominent historical eras, laid the foundation for the esteemed university that CSU is today.

According to the documentary film, “The Great Experiment: CSU at 150,” CSU’s story began with the Morrill Act, signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862. The act granted 30,000 acres of federal land to each state, on which each state had to build an agricultural and mechanical college.

Fort Collins, Boulder, and Greeley all raced to host the new college. In 1870, CSU was established. But in 1874, citizens of Fort Collins donated 240 acres of land and built the Claim Building, a 16 by 24 feet red brick structure and the first building at the college, according to CSU Source. It symbolized a promise to establish the college, since there was still speculation that the college would relocate. Before Colorado became a state on August 1, 1876, what would eventually become CSU was established, then called the State Agricultural College.

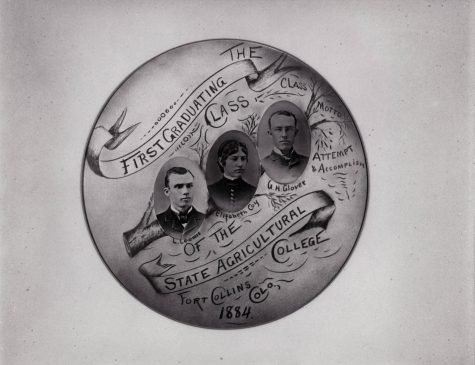

On September 1, 1879, under the direction of the State Board of Agriculture and the guidance of first President Elijah Edwards, CSU opened its first classes to roughly 15 students, including Edwards’ two daughters. Most of these students were 15-16 years old. Frank Boring, the executive producer of “The Great Experiment: CSU at 150,” said that many of the first students didn’t have a lot of prior education because the majority worked on farms.

“At the very beginning of the college, some of [the students] didn’t know how to read or write properly,” Boring says. “They didn’t have the kind of skills that you take for granted to get into college.”

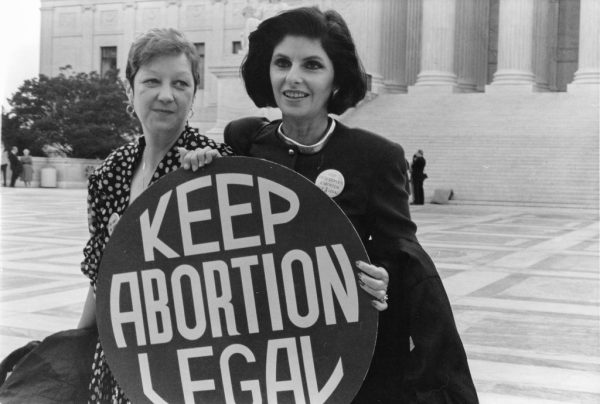

According to Gordan “Hap” Hazard, a historian and CSU alumni, early classes were tailored towards both men and women, making State Agricultural College among the first land-grant colleges to accept women. Men often took agricultural classes and fieldwork, and women often took home economics and domestic arts. However, women also took agricultural classes.

“The land grant, part of [its] mission was to educate males and females and have curriculum that appealed to both of them,” Hazard says.

By 1880, the State Agricultural College became the Colorado Agricultural College. Soon, the Hatch Act of 1887 granted federal funding to the Colorado Agricultural College for an Agricultural Experiment Station, which structured agricultural courses, according to the National Institute of Food and Agriculture. From then on, Colorado Agricultural College became a pioneer in crop experimentation.

“One of the mandates that the State Board of Agriculture told the college president, and basically all the people that work for him, was, ‘We don’t want you to just go out and grow the stuff we know you can grow. We want you to go out and find out what else you can grow in Fort Collins,’” Hazard says.

According to Hazard, The college established experimental crop fields where the present-day Oval is located and found success in crops such as sugar beet, oats, barley, and alfalfa. Students also expanded their work to other areas of Colorado such as Grand Junction and the Eastern Plains. James Pritchett, Dean of the College of Agricultural Sciences, emphasized the success and global impact of CSU’s early crop breeding.

“We’re out in the field and we’re sharing knowledge throughout history,” Pritchett says. “Science evolved, technology evolved, and we started to use the science of technology to help solve agricultural problems that folks had.”

Courses involving mechanics were another big piece of the Colorado Agricultural College. It was such a big piece that in 1935, Colorado Agricultural College changed its name to Colorado State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, or Colorado A&M. Hazard says that to be a successful farmer, one also has to be a good mechanic. Today, mechanics translates to engineering, but in the past, was focused solely on farming equipment and techniques, such as hydrology. Boring says that irrigation technology that originated from Colorado A&M had a tremendous impact on the world regarding water engineering.

“We have taught folks how to make the best use of water resources all over the world, especially in arid and semi-arid environments,” Pritchett says. “Sometimes that’s been large-scale irrigation projects, and other times that’s been around breeding plants for drought tolerance.”

A prominent part of student life on campus was not only attending classes but also maintaining the college itself, according to Boring. Students didn’t pay monetary tuition, but instead worked on campus, whether through completing chores, tending to the farms, or serving as housekeepers.

“You didn’t have to have money in your pocket, but that was part of the deal to be here,” Hazard says. “You had to help take care of the place. Everybody earned their keep here. But the common person could go to college, get an education if they’re willing to do all the work that went into it.”

On January 7, 1893, student-athletes attended their first football game. To rally some school spirit, they needed team colors. On the way to the game, some students stopped at a drugstore and grabbed green and orange ribbons to tie onto their uniforms, thus establishing CSU’s signature orange and green colors. According to the American Football database, they officially started calling themselves Aggies in 1899, which Hazard explains is another term for farmers.

However, the Aggie mascot soon changed. On May 1, 1957, Colorado A&M became Colorado State University. As stated in the documentary, former President William E. Morgan held a contest to name CSU’s new mascot, a ram. However, many students were initially unhappy with the transition from Aggies; as a protest, they voted to name the ram Meathead. But President Morgan overruled the name, and introduced Cam the Ram to the student body. The name “Cam” is an acronym to honor Colorado A&M. Pritchett said that a piece of CSU’s identity lies in its agricultural history and motivation to serve people.

“Part of our identity is as a student service university,” Pritchett says. “When you think about welcoming people to the table, people breaking bread together, making sure everybody has something to eat, that resonates with us. That’s part of our identity that we can be proud of.”

CSU has come a long way from the small agricultural college it began as, and thanks to another former president, Charles Lory, CSU expanded beyond agriculture and mechanics to embrace liberal arts and other areas of study, according to Hazard. Boring says that understanding CSU’s rich history allows one to appreciate the college more.

“We have a very solid history of being open to everybody,” Boring says. “Our evidence of our history needs to be understood so that people coming here for the first time…realize it took a lot to get here. We have evolved not only in our ability to educate, but also in terms of how we deal with each other.”