In February of 2018, a major change in gun control activism occurred. A school shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida led to the death of 17 people and injury of 17 more. The students, exhausted from growing up watching frequent mass shootings, turned to activism to demand legislative action.

While legislation like assault weapons bans failed in the Florida House of Representatives, other forms of gun control like the Extreme Risk Protection Order passed. This law, more commonly known as the “red flag law,” could temporarily halt firearm purchasing. Its success in Florida began a wave of popularity for the bill.

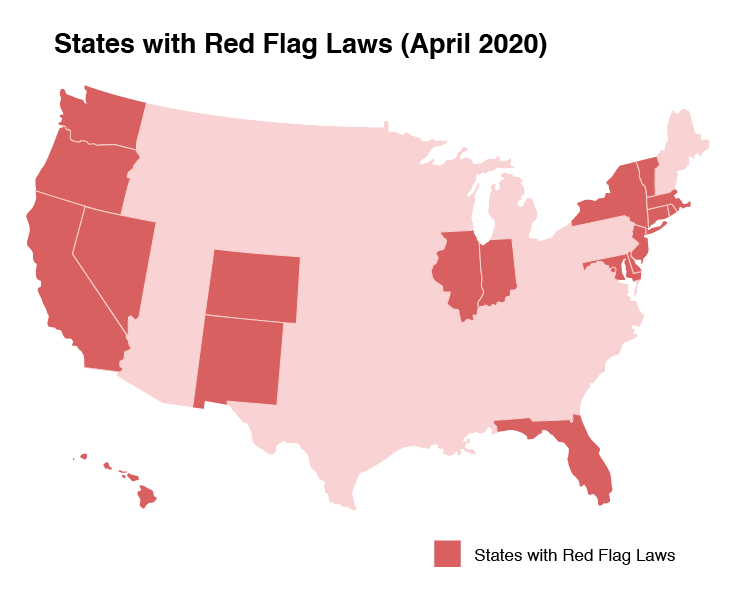

Between 1999 and 2017, only five states out of the fifty had red flag laws. After Parkland, that number has increased to 18 states and the District of Columbia. The “red flag law” comes under a variety of names, including “Extreme Risk Protection Order,” “Gun Violence Restraining Orders” or “Proceedings for the Seizure and Retention of a Firearm.”

The Colorado variation, the Extreme Risk Protection Order, is set up as follows: In the case that an individual makes it clear that they are intending on using a firearm to hurt themself or others, a law enforcement officer or family member may, with evidence, secure a temporary order on that person. If a judge approves the order, law enforcement may confiscate the respondent’s firearms or block their ability to purchase firearms. The request goes through an immediate in-person or phone hearing with the judge, and a full hearing is scheduled in the next two weeks, which could either lead to the closure or extension of the order.

In the case that a temporary order is granted, law enforcement will obtain a search warrant and confiscate the respondent’s firearms.

In Larimer County, the red flag law was used in January of 2020, the same month it went into effect, to stop a man from purchasing firearms after he threatened to commit a mass shooting.

Red flag laws are often seen as laws that address mass shootings. This belief isn’t untrue, but it doesn’t capture the full picture. The law states that it can address any threat of “personal injury to self or others.” Its focus is not just victims of interpersonal violence, but victims of themselves.

Colorado has struggled with its suicide rates for years. The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment has recorded a steady increase in suicides in the state since 2004. In 2017, a rate of 20.4 individuals per 100,000 died by suicide. According to the Colorado Health Institute, the national average was only 13. Colorado ranks 10th in states with the highest suicide rates. Firearms account for half of all our suicides.

Tom Sullivan, the prime sponsor of Colorado’s Extreme Risk Protection law, is one of the Colorado legislators working to reverse these trends. The Aurora Democrat has a personal investment in reducing gun violence. He lost his son during the Aurora Theater shooting in 2012.

Sullivan highlights gun control that respects the Second Amendment as one of his leading values as a Representative. It makes sense he would choose to sponsor the Extreme Risk Protection Order, then. A 2019 study conducted of over 1,000 American adults showed that red flag laws have around a 63.5% approval rate from gun-owners and around a 68% approval rate from Republicans.

Colorado’s red flag law has only been in effect for a few months, so it’s too soon to say if it can influence the suicide rate like it intends to. But, based on studies involving firearm-related suicides and past red flag laws, we can evaluate how a law such as this may help.

The Temporary Removal

Among the most common methods of suicide, suicide via firearms is the most lethal, as it is the most instantaneous. The duration of alternate methods also allows more time for individuals to fully realize and reconsider their actions.

“If they use drugs, gas, rope, anything else, the success rate varies and we have a chance to save them,” Sullivan says.

The difference in fatality rates is steep. A report by Harvard Public Health recorded that attempted suicides that involve firearms result in an 85% fatality rate. The second most widely used method, drug overdose, has a fatality rate of 3%.

Justin Smith, the Larimer County Sheriff, isn’t confident that the removal of firearms will prevent suicide. He says that relying on the removal of firearms as the solution creates a false sense of security.

“If you take away one means it doesn’t mean that they’ve changed their desire,” Smith says. “It just means they could move on to another method.”

However, studies suggest closing off a popular method of suicide can lower suicide fatalities. A recent study by BMC Public Health published in April showed that there is a significant relationship between red flag laws and reduced suicide rates in older populations.

Silvia Sara Canetto, a professor of psychology at CSU, says that limiting the methods most common in a community can be an effective form of prevention. People tend not to switch to a different method if the initial one they had in mind is unavailable.

“People who find a barrier in the bridge they intended to jump from don’t go to a different bridge.” — Silvia Sara Canetto, professor of psychology at CSU

The professor, who holds a Doctor of Psychology in Experimental/Physiological Psychology from the University of Padova, and a Ph.D. of Clinical Psychology from Northwestern University Medical School, uses the example of placing barriers on bridges that are known for being used for suicide.

“People who find a barrier in the bridge they intended to jump from don’t go to a different bridge,” she explains. “Also, they do not switch [methods]. Therefore if you create a delay or obstacle to a culturally preferred method, you can actually prevent suicide.”

Stalling a suicide oftentimes equates to halting a suicide altogether, as suicide is oftentimes a snap decision made in times of extreme distress or emotion.

In a 2001 Houston study, a group of people aged 13 to 34 who had survived a nonfatal suicide attempt were asked how much time had elapsed between the initial decision to end their life and the actual action. Of the group, 86% of those people said only eight hours, and 24% said less than five minutes.

These quick decisions go against the narrative of suicidal individuals planning suicide for an extended period of time. Harvard Public Health reports that suicidal feelings have an “episodic nature” that are engaged in “a moment of brief but heightened vulnerability.”

One of the first cases of ERPO in Colorado involved an officer-instigated order and a Denver man who displayed suicidal intentions. After the order had confiscated two of his firearms, the man commented that he had been “contemplating doing something bad to myself” and that it had been a good thing he had been stopped.

The Removal Process

If removing a gun from the situation helps, then what is the best way to remove that gun? The red flag law directs public safety officials to issue a search warrant to remove the firearms from the target of the order.

Smith raises another concern about enforcement: How do officers navigate these extremely tense situations with people who are already vulnerable? Agitation could be dangerous for both the respondent and the officers involved.

And if a law enforcement agency is forcing this situation, to seize the firearms, you could easily see that go bad.” — Justin Smith, Larimer County Sheriff

An example that came to Smith’s mind was Hastings v. Barnes. In 2002, a man named Todd Hastings called Family and Children Services in Tulsa Oklahoma, seeking help. Hastings was suicidal and needed counseling.

With Hasting’s permission, the Police Department was notified, and four officers were sent to conduct a well-being check. However, the check only agitated Hastings, who did not want to talk to them. Hastings told the officers he was getting his shoes, but instead went inside to grab a samurai sword.

During most of the encounter, It was clear to the officers that Hastings was merely holding the sword defensively. It wasn’t until one of the officers pepper sprayed him in an attempt to get him to drop the sword that he advanced on them, and two of the officers fatally shot him.

Hastings’ brother sued for unreasonable search and seizure and won the case. The judge said that the officers knew that they were dealing with an individual who was “potentially mentally ill or emotionally disturbed,” and that their priority should have been de-escalation. Entering the home and confronting Hastings only worsened the situation.

“There’s a lot of similarities between that and the potential of what could happen with somebody trying to serve an ERPO against a respondent who is suicidal,” Smith says. “They have no intention of hurting anybody else. They don’t express that. And if a law enforcement agency is forcing this situation, to seize the firearms, you could easily see that go bad.”

Catherine Barber, the director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center’s Means Matter campaign, writes that removing or keeping a firearm away from a suicidal person must be based on communication rather than confiscation, which only takes control away from that person during a time of vulnerability.

Preventing someone from accessing firearms in the first place is preferable from having to take them away. This can also be achieved by a red flag order, which places a temporary halt on the respondent’s ability to purchase firearms. The order will also show up on a background check, which would stop the respondent from purchasing any firearms from federally licensed dealers.

An example of using communication rather than confiscation is the Gun Shop Project. The initiative promotes suicide prevention awareness amongst gun retailers and encourages retailers to look for warning signs of customers and put time and distance between suicidal individuals and guns. It includes the gun-owning community in discussions of suicide prevention and has been an engaged and growing initiative in Colorado.

What Else?

When discussing suicide rates, most experts note that there are a variety of external factors at play.

Smith brings up lack of access to mental healthcare. In Colorado, access to mental healthcare often decreases in the same areas that ownership of firearms increases. In rural areas of Colorado, there is one mental health provider for every 1,283 residents, according to Colorado Springs paper The Gazette. In urban areas, there is one provider for every 755 residents.

Dr. David Brent, an adolescent psychiatrist, found that “40 percent of children younger than 16 who died by suicide did not have a clearly definable psychiatric disorder.”

Canetto furthers this idea. In a 2008 article from the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, she documented that suicide patterns across a variety of cultures reveal a stronger association between suicide and cultural narratives than suicide and mental health problems.

“Individuals draw on these cultural scripts in determining their course of action and in giving their suicidal act public significance and legitimacy,” Canetto writes.

In the United States, cultural narratives associate suicide with masculinity and taking control.

“They also make it difficult to think about surviving a suicidal act as a more formidable, more courageous, and more successful behavior,” Canetto writes.

Canetto says changing cultural narratives about suicide would be a more effective form of suicide prevention than a law such as the Extreme Risk Protection Order.

“In many ways, intervening when the person is already suicidal is too late,” she says.

CDPHE report on suicide for the 2017-2018 period incorporates cultural influences on suicide in its strategy to combat suicide.

The report lays out two main objectives: “Targeted intervention and treatment for those at highest risk for suicide and universal upstream approaches designed to impact individuals and communities prior to the onset of suicidal thoughts or behavior.”

As the American public slowly shifts its cultural perceptions of suicide, and the mental health service disparities slowly even out, it seems that the red flag law can offer some immediate relief. A confiscation method is not ideal, but by taking the most lethal method of suicide out of the picture, the red flag law has a very real chance of saving lives.

__________

If you are in need of help, there are a variety of call and text hotlines available to you on a local to national level.

- The CSU Crisis Intervention can be called at (970) 491-6053 and after-hours counselors can be accessed at (970) 491-7111.

- Colorado Crisis Services can be reached by calling 1-844-8255 or by texting “TALK” to 38255.

- The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be called at 1-800-273-8255.