Ad

Behind the Send

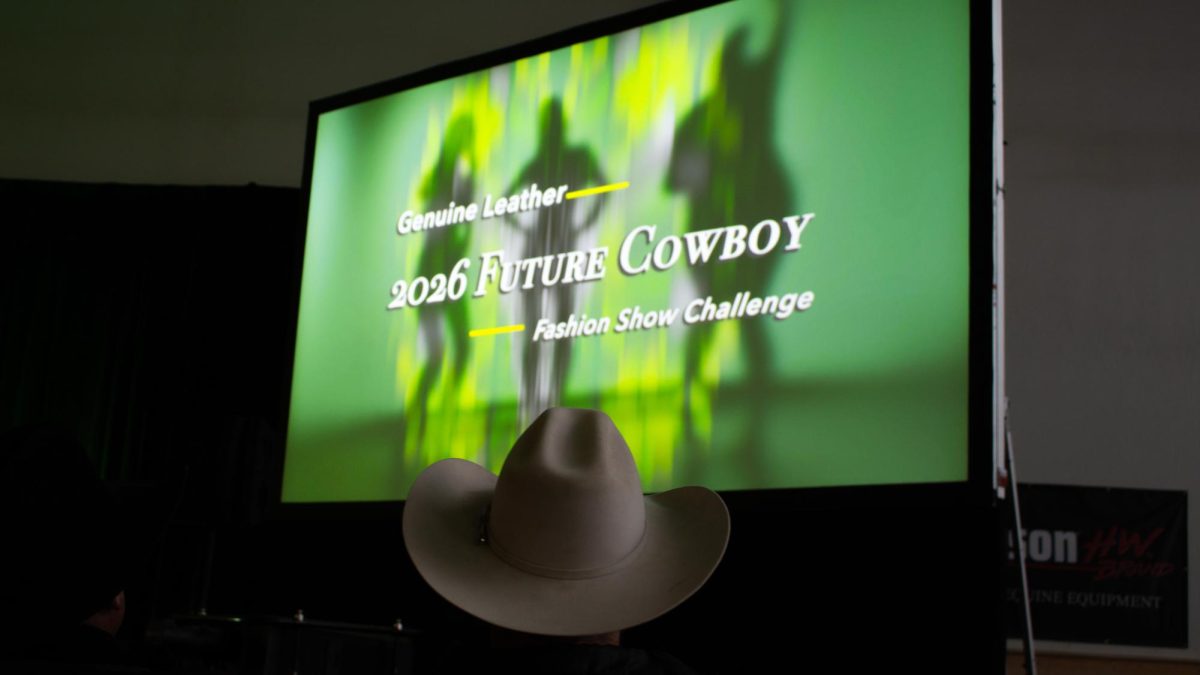

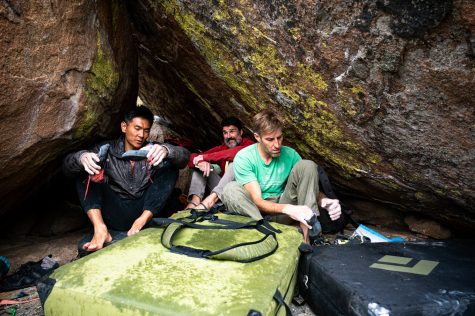

Ben Scott cleaning off a new boulder in Red Feather Lakes Oct. 14. (Milo Gladstein | College Avenue Magazine)

November 9, 2022

The crew piles into a Sprinter van with pads, shoes, chalk, beer, weed, and everything needed to have a successful day out climbing. Old-school rap music sets the tone in transit to Red Feather Lakes. On the way to the boulders, weather is assessed as clouds roll in, and dogs bark in the back of the van. The day starts by scouting out new boulders and billy-goating along the cliff.

Just as the crew gets gear out to climb, it begins to rain. Ben Scott, Dan Yager, and Jason Tarry take shelter under trees and boulders.

“Well, what now?” Yager asks.

“I don’t know,” Scott replies. “Guess it’s time to smoke some weed and wait it out.”

In between trying routes, climbers share jokes and talk about a variety of topics, often discussing sports, work, or the meaning of life. Jokes are made, joints are smoked, beers are downed, and everyone is constantly laughing. But once the shoes come on, holds are brushed, and hands get chalked, the switch gets flipped and it becomes an entirely different activity.

Climbing demands dedication and persistence to succeed. “Sending” is the term climbers use when they finish a route. “Projects” refer to challenging routes picked very meticulously. Once a goal is set, it’s as if a switch is flipped and it’s time to buckle down and get serious.

Yager breaks projecting down into three steps: solving each move, unlocking clipping positions, and linking pieces. The first step refers to conceptualizing body positioning and sequence for the route. Days, weeks, and sometimes, in extreme circumstances, years are spent calculating each and every move, scrutinizing over each crystal on each hold, finding all the crucial footholds, and eventually memorizing each sequence. Next, unlocking clipping positions protects the climber as they ascend the route. The rope is clipped into a quickdraw, consisting of two carabiners joined by a webbing. Projecting often feels like putting together a puzzle. The final step is putting the puzzle together. Each piece is laid out in front of the climber, who then must link all the pieces together.

Climbers find a project that is special to them either, through developing a new area or looking through a guidebook. “Developing for me, it’s finding something that’s never been done,” Tarry, a lifelong climber, says. “It’s the first man on the moon…. That itch, that drive that makes you want to see what’s around the bend.”

Guidebooks help climbers navigate an area and pick projects. Ben Scott, president of the Northern Colorado Climbers Coalition (NCCC), has written the Poudre Canyon and Red Feather Lakes guidebooks.

“To me, it’s always been about sharing,” Scott says. “Ever since the beginning, I’ve always been interested in guidebooks and sharing media and just trying to promote the psych.”

There are many challenges that come with guidebooking for Scott.

“You have to really put yourself in the shoes of someone who’s never even heard of Red Feather Lakes before, and how they’re going to understand the area and break it down and find everything,” Scott says.

Many climbers have put years into their pursuit to improve and progress in the sport. Dedicated climbers train for hours a week. it can become almost like a second job due to the dedication the sport often demands. This can often lead many climbers to attach their worth to how well they perform on the rock; when an attempt doesn’t go as planned, it can lead to breakdowns, screams, and tears.

“(Projects) have to be really special to get to that top echelon, and you have to train really hard,” Tarry says.

Climbing is intense both physically and mentally; it demands every ounce of effort and focus. Yager, former MMA fighter, American Ninja Warrior competitor, and board member for the NCCC, found a passion for climbing.

“After retiring from mixed martial arts, I was in search of something that fulfilled me physically and mentally that challenged being in the cage, and I found that on the rock,” Yager says.

Many climbers have projecting down to a science that works specifically for them. This includes detailed training plans based on what the specific route demands, mental training, and time management skills. For people who have families and jobs, it is important to take advantage of every opportunity you get on the rock and in the gym to maximize effort.

“It’s mental training focused on a singular goal,” Tarry says. “In order for me to stay focused on a singular goal, it’s everything from documenting the sequence in a journal, to trying to replicate the sequence with some holds on my home wall, to working specific power based on the moves required in the route, (to) using the bouldering gyms to work on that power endurance.”

Along with the mental training comes the physical demands. There are many physical aspects that are important for climbing. “Power” refers to being able to generate enough strength to make a big, explosive move. “Power-endurance” is how long a climber can sustain that power. For Tarry, power takes priority, followed by power-endurance and, finally, endurance. Rest is an important part of the process to insure recovery and steady progression.

“(Power endurance is) the first thing that I noticed goes, being able to maintain a high level for an extended period of time,” Tarry says.

Climbers invest time, thought, and preparation before sending a project. As important as it is to perform move after move, resting on a route is just as crucial. Taking a second to take some deep breaths and gain some strength back can be the difference between sending and falling.

“Calm the heart down and calm the breathing down,” Tarry says. “Because if you can calm it down, then you can perform at your peak again. It’s about being able to execute, execute, maybe get a quick shake, and then execute again.”

Once the groundwork is laid out, it is time for a send attempt. This calls for an entire plan itself. When projecting, climbers often get into a groove of certain days to get out and try their project. They get up early, eat the same breakfast, and head out to the cliff. Once at the climb, the same warm-up routine leads to send attempts. Projects can last anywhere from days, to weeks, to months, and even years.

“Ben and I bolted Ivory Tower a decade ago,” Tarry says. “It’s a two-pitch climb, and when we saw it, we said, ‘that’s the line to do.’ It was scary, it was windy, and you had to jump across this gap to the detached block, so it’s kind of an epic just to get there.”

When the route was first bolted 10 years ago, Tarry couldn’t figure out one sequence on the climb. It was beyond his ability. Coming back to it after a decade, he completed the sequence, putting each piece of the puzzle together to send the route.

There is so much that goes into projecting and developing. It is important to look at every piece of the puzzle, train hard, flip the switch, and send. The time dedicated to training and solving each and every move, to taking time after work to train, to perfecting a ritual and ultimately having the drive to stick with it for as long as it takes to send; climbing at a high level takes much more than meets the eye; it is the ultimate test of dedication.