Everyone recognizes the mascots of the Democratic and Republican parties: America’s donkey and elephant. Losing all zoological significance to serve in a political circus, they have evolved from silly cartoons to characterizing a battle for a nation. So, where did they come from and how did these drawings become the icons we know today?

Unlikely Beginnings: Cartoons and Mockeries

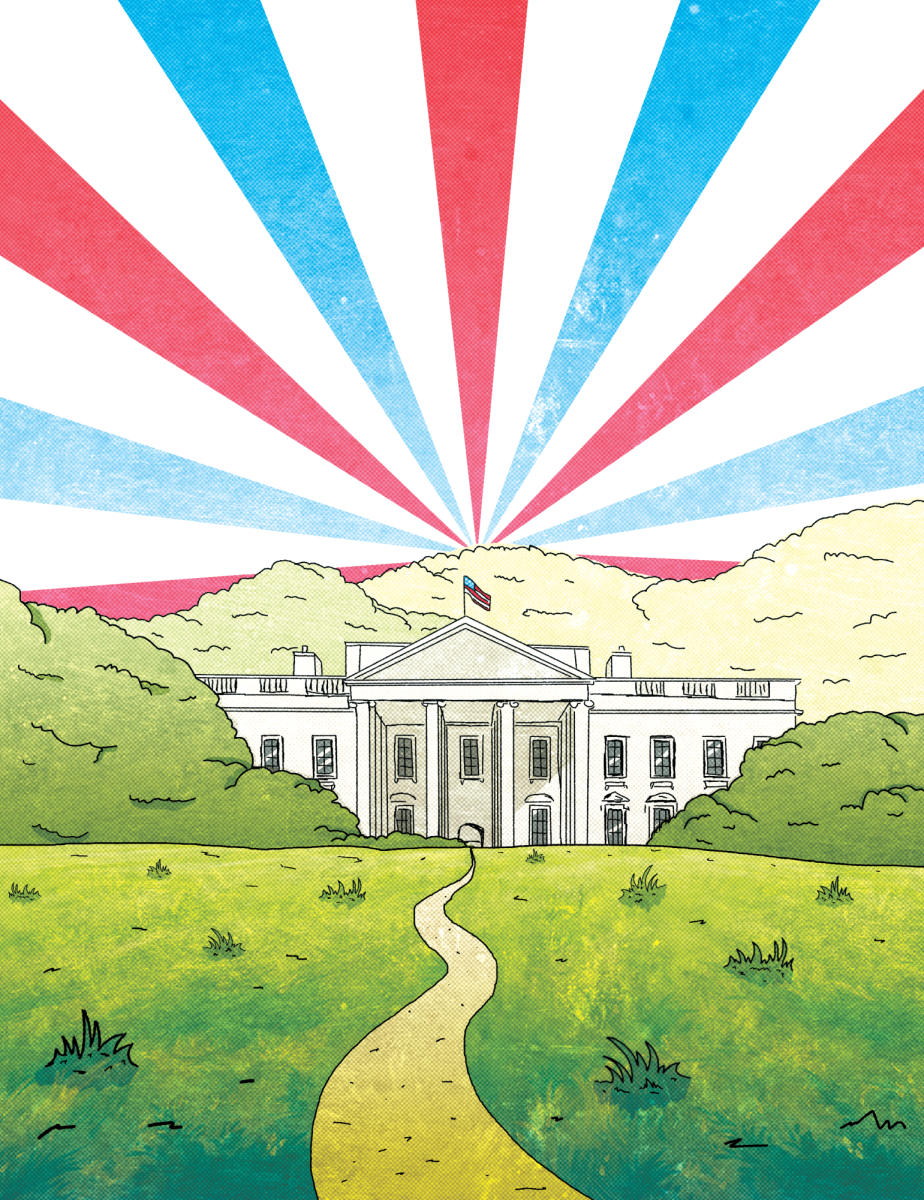

Many historians credit Thomas Nast, a cartoonist from Harper’s Weekly, with popularizing these caricatures. Largely known for his popularization of Uncle Sam and the contemporary image of Santa Claus, Nast was eventually coined the father of the modern political cartoon. A master of the medium, he used his vast political knowledge to infuse his illustrations with ink and carefully crafted political propaganda.

His most popular illustrations became those that created satirical parallels between interest groups and wild animals. Though he was not the first to use these symbols to ridicule candidates, Nast’s nonpartisan critiques of both the Republican and Democratic parties brought to life a new form of exposé.

By using these animals, Nast emphasized the distinct qualities of each party. Often an elephant would be depicted as strong but clumsy, painting the Grand Old Party’s size as a weakness. While the donkey was often strong but hard-headed and caught up in its own stubbornness. All boiling down to one main idea: chaos.

This begs the question: Why did the parties choose to embrace the mockery of Thomas Nast and other satirical cartoonists?

Colorado State University’s History chair and professor, Robert Gudmestad, says “…it was probably easier for them to shift the meaning than find a substitute.”

Having established mass popularity, it would have been incredibly difficult to force the symbols out of popular culture. Instead, each party chose to capitalize on the existing recognition in the public eye.

Often used to garner support, interest, or ridicule for a topic, illustrations had profoundly impacted the sociopolitical views of the population. During the 19th century nearly 20% of the adult population was illiterate, making the expression of ideas through these illustrations an effective tool for education and outreach.

People still see this effect today. Though they do not often come with the same connotations, elephants and donkeys continue to parade through the political landscape, often depicted on posters, merchandise, websites, and more.

The Democratic Donkey

Stubborn, courageous, and tough—qualities that define a donkey and by extension, the Democratic Party.

Dating back to 1828, this symbol initially emerged during Andrew Jackson’s second presidential campaign when he ran as a Democrat. After losing to John Quincy Adams in 1824, Jackson ran for the strength of the people, straying from the Democratic-Republican party. During this election, his opponents called him a “jackass,” to which Jackson chose to embrace the nickname and included donkeys in his campaign posters – and won.

Though the association slowly died after Jackson’s presidency, Nast reintroduced the donkey nearly 30 years later in an illustration titled “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion”. This piece, sketched precisely as titled, served as a commentary on the hostility of Democrats towards Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of war. From then onward, him and other satirical/political cartoonists used the beast within their art to taunt the democratic party. For instance, an 1879 cartoon Nast published for Harper’s Weekly depicts a distressed donkey dangling by the tail over an abyss of financial chaos.

The Republican Elephant

The Republican elephant first appeared in 1864 in a pro-Lincoln campaign newspaper called Father Abraham. The advertisement featured an elephant flaunting a banner that read “The elephant is coming”, which celebrated Union victories during the Civil War. This phrase was rooted in the expression “seeing the elephant” which soldiers used to mean engaging in combat and an acknowledgment of the formidable challenges ahead.

As a result, the association between the elephant and the Republican Party surged, initially linking the party to power and determination.

However, once satirical artists got hold of the image, they quickly tore at any faults they could find. They often portrayed elephants with big ears, trunks, and feet along with a clumsy demeanor, surrounded by destruction or disarray.

In 1874, a decade after the initial appearance, Nast published “Third-Term Panic” to depict the anxieties around rumors that Ulysses S. Grant would be running for a 3rd presidential term. The illustration portrayed various political groups as animals, most notably a donkey wearing a lion’s skin branded with the word “Caesarism,” startling an elephant labeled “the Republican vote.” The strong intelligent creature is bested by its size. Often, this illustration is credited with cementing the connection between the two, making the elephant a lasting party symbol.

Why have they stuck around?

These mascots remain very prominent today. Thanks to 19th-century political cartoonists, they appear without a doubt every election cycle in countless illustrations, advertisements, merchandise, and more.

“…Mascots [may] have remained prominent because they are like mascots for sports,” Gudmestad said. “Mascots are shorthand for saying that I believe in certain things.”

In the same way that teams make people part of a larger group, mascots foster a sense of community among party members. So, it is easy to see why politicians continue to use these symbols, creating unity and loyalty among their supporters.