Ad

Fire Suppression and Climate Change: Is this the End of Natural Forests in the West?

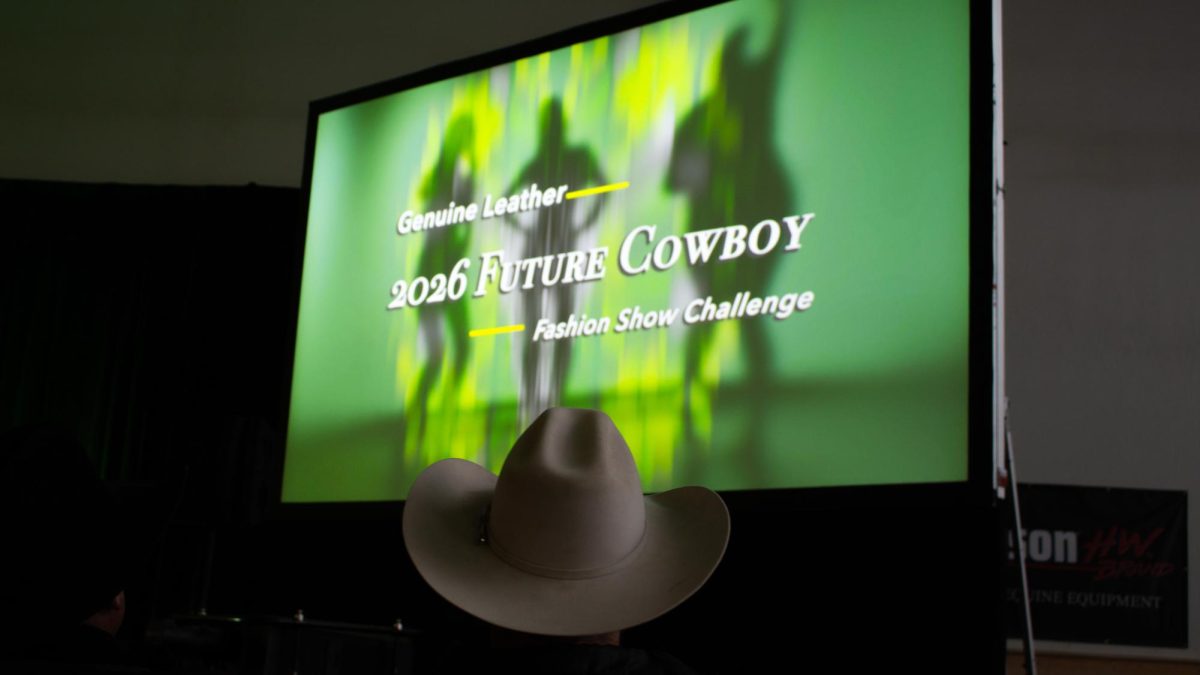

The Bradley fire burns on the side of the road as firetrucks line up to fight it. (Photo courtesy of Christian Hullet)

January 28, 2022

Chris Hullett had just finished his last day of battling the California Lava fire on July 11, 2021, with his strike team of five fire engines. He was looking forward to getting off early so he could go home and rest. With only 20 minutes left in his shift, dispatch rang out:

“Approximately 150+, moderate intensity, moderate rate of spread, potential to go big.” Hullett knew then that his day was far from over.

“The scene of a fun initial attack is like a Call of Duty mission,” Hullett, a former forestry technician on the fire suppression crew for the Tahoe National Forest, said.

Hullett and his team run their lights and sirens through the orange haze until they get to the edge of the Bradley Fire. With the long hose connecting the water source from the truck, Hullett begins to walk on foot further and further into the smoke, aiming the hose at the base of the flames. Tankers streak the sky with blood-red retardant, and helicopters zip above him, dropping water that erupts into smoke when it hits the ground. Bulldozers move in to pave a fire line and the ground begins to shake. Hullett’s mouth is dry and his ears feel like they’re melting off.

In 2020, 59,000 wildfires blazed across the United States, according to the Congressional Research Service, and 10.1 million acres burned. In 2021, 6.5 million acres burned. This may not have been a big deal over 100 years ago when the trees and shrubs below the canopy would be rid of their dead brush and decaying matter, pine cones would expand to spread their seeds and the forests would return taller and healthier than before.

But now, in the West, forests are not coming back.

Climate change coupled with decades of suppressing forest fires are changing the land use in the West. Burned areas where there once was tall spruce fir and lodgepole pine are growing back as grasslands or brushlands, forcing forest managers to shift their plans from managing forests to replanting forests. It has been decades since the nation’s fire troubles began with the Great Fire of 1910. And they are far from over.

The start of fire suppression in the United States

The Great Fire of 1910 ignited seemingly everywhere. Drought parched the American Northwest, and heavy winds along with lightning strikes caused hundreds of fires to erupt in the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana. They culminated into one big burn, overwhelming the newly established United States Forest Service (USFS). With not enough front line workers or adequate protocols, the USFS partnered with the United States Army to attack the fires. Still, the wildfires burned 3 million acres across Idaho and Montana and claimed 87 lives, most of whom were firefighters.

This is when the “10 a.m. policy” was enacted. All wildfires had to be put out by 10 a.m. the next day, and the USFS began its war on fire that would last a century.

Ecologists maintain that fire is a natural and vital ecological process, not to be conquered to protect the timber industry or the profit it provides.

Public information campaigns such as Smokey the Bear, children’s songs and posters stressing to protect the timber supply said otherwise. The effects can be seen today through intense fires that envelope the west and save no one from the devastating effects that come with it.

“There were all these perceived benefits of putting fire out and then there was Smokey the Bear, and this kind of multimedia push, even back then, to try to educate people (that) fires are horrible,” Tony Cheng, professor in the department of forest and rangeland stewardship at Colorado State University and director of the Colorado Forest Restoration Institute, said. “It’s almost your patriotic duty back in those days to prevent fires, to fight fires and to support the fire suppression policy.”

Wildfire management today

Now, the USFS acknowledges that wildfires must burn, while still maintaining that fires are a threat to life and property, especially on the wildland-urban interface. Instead of resorting to complete fire suppression, the USFS has switched to more emphasis on fuel mitigation and communicating with local agencies and the public.

“How we used to manage fires was not right,” Zachary Ruther, a seasonal forestry technician on the timber crew and firefighter in the Palisade Ranger District in Idaho, said. “If you talk to anyone in the forest service they’re going to tell you that. We have all this build up of fuel and it’s leading to unhealthy forests, which is creating more stress on these trees and just making everything super susceptible to fire.”

Logging is one practice used to thin forests so that the remaining trees can grow bigger and healthier, and therefore be more resilient to future fires. This is most effective followed by prescribed fires, or controlled fires that are purposefully lit to clear out dead matter and dry vegetation that pose as fuel for larger fires. The USFS has increased the amount of prescribed burns they do, but with climate change causing longer, hotter summers and shorter, warmer winters, the burn window where conditions are suitable to practice prescribed fires gets narrower.

Thinning forests are short-term solutions, but practicing prescribed fire in those areas eliminates the fuel left from logging and enhances forest health for the long-term. Prescribed fires are vital in replenishing the forests that have been suppressed from burning for so long. There are many other factors that get in the way of prescribed burns, such as air quality rules, social acceptance from surrounding communities and whether there are enough workers and supplies to get the burns done. According to a natural resource history and policy lecture on Nov. 18 by CSU Associate Professor Courtney Schultz, 98% of fires in the U.S. are still actively suppressed.

“The forests haven’t been adequately managed in years,” Hullett said. “But it’s a really big responsibility that the government just doesn’t have the manpower or money for.”

Ruther says that the number of wildland firefighters are dwindling, and although Hullett emphasizes that firefighting is the best job he’s ever had, he quit because he wanted a normal life.

“For the hours we work, for the duration we work, for how often we’re away from home, they don’t pay you a whole lot, and people are just getting sick of it, because they’re risking their lives,” Ruther said.

According to Schultz’s lecture, 60% of the USFS’ budget is used for fighting fires, up from 30% since 2000. The more wildfires that happen, the more workers are needed, but the risks are too high for many firefighters compared to the benefits. Both Cheng and Schultz place an emphasis on working with local fire agencies and educating landowners so that they can have the skills and knowledge that fire crews have.

“That might mean potentially raising taxes to fund more fire management crews to be able to manage fires in a different way. (Or) to maybe think about ways of steering a fire rather than attacking a fire. Every time we do that we are setting that land up for the future to be able to recover and be more resilient to fire the next time it happens,” Cheng said.

“The biggest thing is we have to create communities that are ready to live with fire. So (communities) that are clearing around their homes and then getting comfortable with prescribed fire,” Schultz said. “I think we’re like a hundred years behind the curve in terms of fire suppression, and then we have climate change. So I personally think a lot of these forests are just going to burn, and we have to start thinking about how we’re going to restore post-burn landscapes effectively.”

The disappearance of forests

Forests are burning, and they are not as expected.

“All of our forests have been adapted to recover from fires,” Cheng said. “But the kinds of fires we’re seeing as well as the changing climate is creating these conditions where we’re not seeing seeds established and new trees growing. So we’re seeing a conversion from forest to something else.”

Cheng said that the size of these wildfires are burning all of the tree’s seeds, and even if there were seeds, climate change is creating conditions that are too hot and too dry for the seeds to establish. “Unless we as humans invest in growing trees in greenhouses and then transporting them out to the forests to plant them at huge costs, we’re not going to see those areas coming back naturally.”

Forests act as carbon storage, something that is increasingly needed as the atmosphere becomes overwhelmed with carbon dioxide.

“A lot of carbon stays in the forest in the dead trees and the soil,” Schultz said. “But what we lose are wild forests that can sequester carbon and act as carbon sinks, so our forests here in Colorado are becoming net carbon emitters, rather than carbon sinks.”

Climate change is contributing to a cumulation of other factors that are making it harder for forests to grow back. Bark beetle infestations paint the trees in patches of decaying red until there is nothing left except gray, shriveled trunks, something increasingly seen because winters are not getting cold enough to kill the beetles.

According to the USFS, bark beetles chemically alter trees, drying them out and making them more susceptible to fire. Similarly, drought weakens conifers’ ability to repel bark beetles, creating a cycle that favors beetles and hurts trees. Models suggest that beetle-infested trees increase the rate of wildfire spread, because the red, decaying stage of the needles are more flammable than healthy, green needles.

Forests are also important water absorbers. Without the canopy capturing rainfall, burned areas are much more likely to flood and cause landslides, such as the one in July that killed four people in the Cameron Peak burn scar area. With added sediments seeping into water supplies and floods destroying structures, the cost of constantly repairing damages caused by wildfires will continue to mount.

“We need to start incorporating the cost of reforesting after fires,” Cheng said “We’ve always counted on the idea that forests will naturally come back after these fires, but we’re not seeing that. So if we want forests in places that have always been forests, we as humans need to invest in that, so that’s a management decision that has a lot of financial implications.”

The USFS has come a long way in recent decades when it comes to forest management, and there is still a long way to go. It takes more than the federal government to manage wildfires and maintain healthy forests. It takes cooperation between communities, landowners, local and state fire agencies and more.

“We need to sort of get beyond this notion that all fire is bad,” Cheng said. “It’s not a black and white thing, but that’s hard to do and people would rather see black and white than shades of gray. The more people that can see the shades of gray the better.”